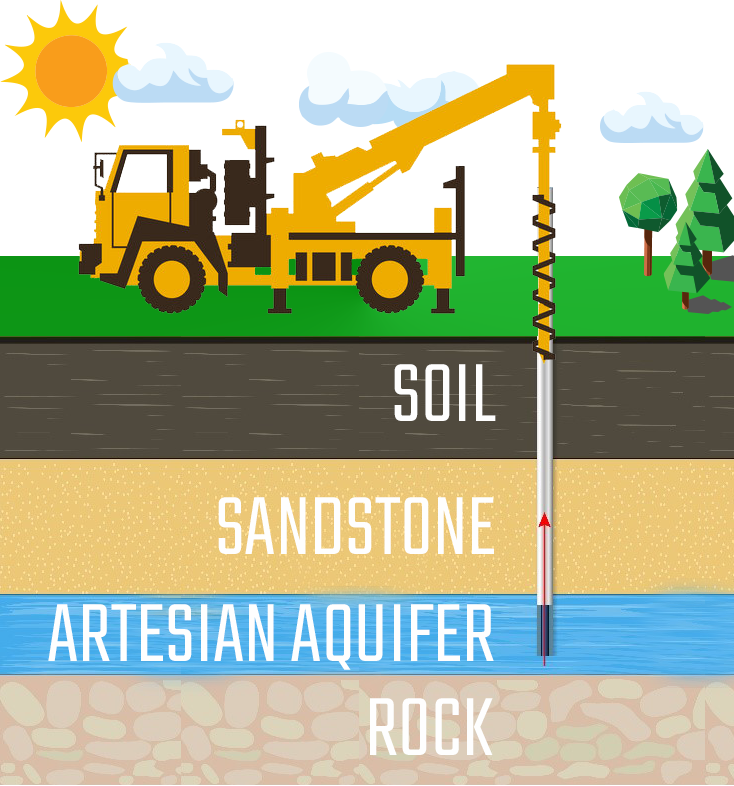

Two methods typically used for drilling water wells are rotary and air hammer.

Down-the-hole drilling (DTH) essentially involves a drilling hammer at the bottom of a drill string. It relies on three elements for drilling holes: bit loading (weight), rotation and air. These active elements combine to be efficient at crushing rock. As the drill string slowly rotates, the drilling hammer is forced into the rock repeatedly. Striking power is provided by compressed air driving a piston inside the hammer.

The DTH hammer is pneumatically powered, with the compressed air propelling it forward to impact and fracture rock. Compressed air also travels through the drill bit into the hole (air exhaust), which blows the chips and dust out of the hole.

No matter which method of drilling is used, the top part of the well is usually lined with steel or plastic well casing.

The diameter of the drilled hole is usually an inch or two wider than the diameter of the casing. The space between the drilled hole and the casing (the annulus) has to be filled to prevent the chance of polluted surface water from migrating downward along the outside of the casing where it might contaminate the aquifer.

This filling is called "grout" and (depending on local regulations) it may be either cement or special volcanic clay called bentonite. Sometimes most of the space is filled with the fine rock pieces from drilling and then the top 20 feet is grouted. The design of the well and its completion after the hole is drilled will be the subject of the next article in this series. A modern water well is much more than a hole in the ground.

QUINCE M PRO

QUINCE M PRO